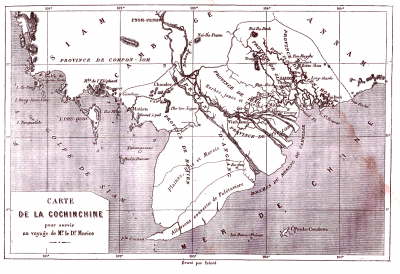

canals in the delta

The Mekong delta has been the stage of large canal works since the beginning on the 19th Century, well before the French arrived. In the 1850s, the Vĩnh Tế canal, between Tân Châu and Hà Tiên on the Gulf of Siam, was an established trading route to Thailand.

You can still navigate part of the Vĩnh Tế canal today.

Canals silt up naturally: with the ebb and flow of brown water, each tide cycle brings a fresh layer of sediment in the middle of the canal and eventually forbids the passage of larger boats. The French saw the Vĩnh Tế canal as a threat, opening for the Thai a way into the region, and abandoned it. Today, even dredged, it is navigable by smaller boats only.

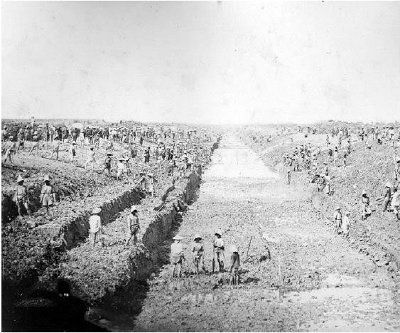

Canal works required dozens of thousands of people, and the working conditions were very hard, claiming many lives for the digging but also for the maintenance of the canals, which took hard labor year after year and each time meant interrupting traffic. Only canals meant for transportation were worth digging.

When the French had the Canal Duperré dug, by Vietnamese hand labor, it was designed with ease of maintenance in mind: the canal had a sedimentation basin to receive the deposits of alluvium carried by the canal water. From then on, dredging the basin was sufficient to keep the canal deep enough, and could be done without interrupting the traffic. This was hailed at the time as the first forever canal.

Now Kênh Chợ Gạo, the rice market canal, it is still today the main river passage to Ho Chi Minh City, between Mỹ Tho and the Vàm Cỏ river. Its design survived 130 years and it is as wide today as it used to be then.

Steam dredges

After France became a republic in the 1870s, the governance of the colony was handed from the admiralty to a civil administration whose mission included nation development: the mission civilisatrice1). As part of this effort, the colony committed steam dredges to dig canals, not only for trade and warfare, but also to help drain floods and make agriculture more practical.

We can take you to visit these canals.

The dredges made it possible to farm unused land, and local inhabitants flocked along the canals for the of access as well as for the new land. But other areas were well cultivated and needed the tides for irrigation; the new drainage through canals affected that, and forced farmers to change their ways, which steered resistance.

The dredges also cut new ways for the steam boats to access the delta quickly, and thus took trade away to the benefit of colonial companies, like the Messageries Fluviales de Cochinchine.

So the steam dredges deeply disrupted the prior status quo, and people would take sides for or against the French.

Little remains of the half-dozen dredges themselves, but the pattern of canals near Long Xuyên or between Cần Thơ and Hậu Giang make for very nice visits.2)

- Many thanks for David Biggs, and his tremendous work, Quagmire, Nation Building and Nature in the Mekong delta.

- Photo credit: David Biggs; Nhân Dân online