Traces of history

Cửu Long, the Mekong in Vietnamese, means Nine Dragons

- If you are interested in today's geography, see the Mekong delta.

The nine dragons are alive

In Vietnamese, the Mekong is called “Cửu Long”, which is Sino-Vietnamese for Nine Dragons, after the number of its mouths, but as you try and count the branches of the Mekong that actually reach the sea today, nine is one of the few numbers you will not reach. The dragons are moving.

With the siltation and erosion from the sea, the rains and its own flow, the Mekong is changing and evolving. Islands propagate, oxbows appear, mouths silt up.

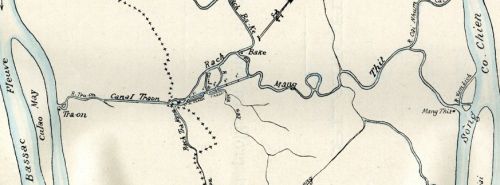

It takes an old map to figure out the origin of the nine dragons, like this one, dated circa 1910, where we see the following mouths: on the Hậu Giang river, alias the Bassac, are the Đình An, Bassac and Trân Bé mouths, or Cửa. The Cửa Đình An is the trading way today, although so much sitled that there is now a project to open a separate canal through Trà Vinh for the larger freighters. The Bassac mouth is now completely silted up and disappeared.

The rivers Cổ Chiên, with Cửa Cung Hậu and Cửa Cổ Chiên, and Hàm Luông with Cửa Hàm Luông, are still there and are similar today to what they were in the early XXth Century. Tremendous change occurred on the Mỹ Tho river, the end of the Tiền Giang: the Cửa Ba Lai, which was the end of its own river, was entirely silted up and the river nearly completely disappeared, into what is now known as Bình Đại district, in Bến Tre. Cửa Đại and Cửa Tiểu, the large and small mouths of the first river, are still here, Cửa Đại being the main commercial route towards Cambodia today.

Historic waterways

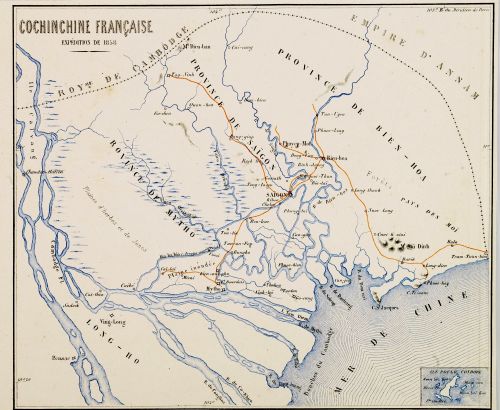

Since the French arrived in the then Cochinchina, they were tempted to open routes to upstream the Mekong delta into Cambodia and then Laos, and as early as 1858, at the time they landed in Tourane (Đà Nẵng), they launched a reconnaissance expedition to chart the larger ways of the Mekong delta, much earlier than the famous Doudart de Lagrée exploration in 1866.

If the geography and proportions of the rivers differ a bit from reality, their topology is rather correct, as far as navigators of the main arteries could discover at that time. Cù Lao Giêng, Cù Lao Ông Hổ, Cù Lao Mây, many details of the Mekong topography are present, and we can somewhat rely on the map to appraise the evolution and changes of the river and its trading waterways.

a steamer named Bassac was navigating the region at that time already.

Many of the main canals are not there, especially Kênh Chợ Gạo and Kênh Lấp Vò, between Mỹ Tho on the Mekong and the common trunk of the Vàm Cò rivers (here named Vai Co), but there are some rạch and arroyos that were at that time of commercial use and that have since become quite secondary, as the Kinh Ba Bio, between Saigon and Cái Bè. The river Măng Thít, between Trà Ôn and Cổ Chiên, is not charted, but its mouth at the confluent on Cổ Chiên (then Co Khiên) is present on the map. The Trà Ôn canal, which was to become the Nicolai canal later in the XXth Century, was certainly already there, at least in its original, river form.

More importantly, there seems to be a natural connection from the first river to Cổ Chiên, just upstream of the effluence of Hàm Luông, at about the location of the present day's Chợ Lách canal. The canal runs 6km across the An Bình peninsula, which is nearly 2km across at its thinnest. Could there have been a natural connection? Maps of 1910 show the canal as it is today, Could it have silted up that fast? Maybe it could: a rather complete map dated 1929 does not show it, nor any connection.

Was Cần Thơ named "Bassac"?

When we named our boats the Bassac, we were referring to the older name of river Hậu Giang, the second but larger branch of the Mekong, that originally splits from the main Mekong flow at Phnom Penh, and then grows into its largest tributary.

According to this map, it seems the name Bassac may have originally been given to the town of Cần Thơ, our home. Could it have then evolved into the name of the river?

This very map shows very clearly how the topography of the delta evolved: we can see how the connection of Măng Thít river was protected by being inside the long curve of Cồ Chiên and is essentielly the same today; we also can see how Bình Hòa Phước used to be an island –today a long peninsula crossed by Chợ Lách canal.

A fine mesh of canals

Many canals were not built as planned

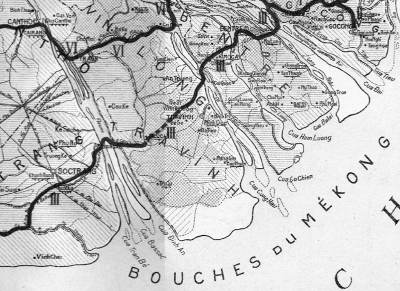

The map shows in red the primary waterways, and in blue local waterways.

There is a passage at Chợ Lách, between Cái Bè and Cổ Chiên river, and the Kiên Lương canal was already between Châu Đốc and Hà Tiên on the Gulf of Siam. Many waterways that were deemed of general interest are now limited in air draft by low bridges, and only run by smaller freighters, as for instance the straighter way from Bạc Liêu to Mỹ Tho.

In dotted lines on the map are the canals that the colonial administration planned to dig at that time. With the advent of 1925 and the beginning of social unrest, many of these canals were never built. And some as well should not, like a canal from between Long Xuyên and Châu Đốc that would have met the sea halfway from Rạch Gía to Hà Tiên, where there is nothing. The present day Kênh Rạch Sỏi makes much better sense.

A historic capital of the delta?

An extended network of local canals and waterways shows in blue on the map, although mostly in dotted lines, so as projects at that time. It is quite noteworthy that most of the larger existing canals of local interest as drawn on the map lead to the same place: Phụng Hiệp, about 35 km South of Cần Thơ, and which still hosts today one of the largest floating markets of all: Ngã Bảy, which means 7-ways crossroads (see a satellite picture). If the map is complete enough and reliable, it hints that Phụng Hiệp may have been quite an important commercial place at that time.

Our boats, the Bassac, have all been built a few hundred meters away from Ngã Bảy, in Phụng Hiệp.

David Biggs, arguably today's historian most knowledgeable of the Mekong delta, has dug out court cases showing we in fact owe the French engineers numerous canals leading to Phụng Hiệp: the later ones having been excavated under legal pressure from the local land owners to try and alleviate recurrent floods brought to the area by the former ones. See David Biggs' Quagmire, Nation building and Nature in the Mekong Delta, 2008.

Treading forgotten meanders

On the way from Cần Thơ to Cái Bè or back, we run along Măng Thít river and Nicolai canal. Both were present in the early XXth Century, as we see on this map dated about 1910.

The Nicolai canal was then named Trà Ôn, after the town at its confluent with the Bassac, behind Cù Lao Mây, where we stop for floating markets on the way to Cần Thơ in the early morning. It is much straighter than a river, which not only makes it faster to cross, but also protects it against the sheer force of erosion.

Where the path becomes a winding river, we reach Măng Thít, still a very beautiful sight today. The meanders of Măng Thít river evolve year after year and are more marked today than they were then: silt settles on the inside of curves, whereas the water erodes the outer bank of a meander, carving it out in the long run. This translates in the folk's voice into a saying about the comings and goings of life: “dòng sông bên lở bên bồi”, “rivers carve one bank, fill one bank”. The map actually shows a meander so bent that a shortcut appeared or maybe was dug, leaving out the loop of the river.

Visit an oxbow of Măng Thít

A hundred years later, the loop has turned into an oxbow. It is still there (see a satellite picture), but shallower and narrower, and it actually defines a beautiful biking path, as the middle of the “islet” is open ricefields circled by coconut trees. On some trips, the Bassac stop there for a stroll and a visit on shore.

![[map] Colonial and local waterways, 1910 [map] Colonial and local waterways, 1910](https://mekong-delta.com/_media/en/places/local_waterways_1910.jpg?w=500&tok=19247e)